Table Mountain: A Model of Self-Sufficiency

Published on Canadian Ski Hall of Fame & Museum | skimuseum.ca

If our children are the lifeblood of skiing, then community ski areas are its heart and soul. Often small and remote, they’re where most of us once learned to ski. And where we’re now introducing our children and grandchildren to the lifelong joys of our favourite winter sport. Community Ski Areas examines the past, present and future of Canada’s community ski areas. | Creative Director: Gordie Bowles | Writer: Dave Fonda

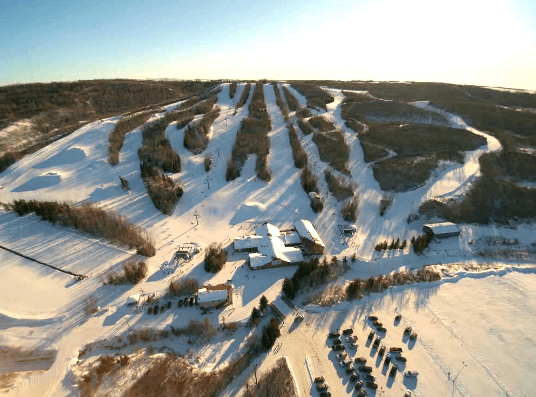

Running a ski hill isn’t easy. You’re constantly coping with unreliable weather, rising insurance costs, an aging infrastructure, transient workers, a tenuous supply chain and who knows what else. Now imagine having to handle all that without having a great vertical, or a majestic mountain setting or epic dumps of powder snow. Welcome to Table Mountain, Saskatchewan, where self-sufficiency isn’t just a clever catchword. It’s the key to their enduring success.

The Lasting Power of Foresight

In 1964, Irwin MacIntosh, Dr. Zacharias, and four other businessmen founded the Battlefords Ski Club and started skiing in the McMillan gravel pit in North Battleford, Saskatchewan. Their folly was an instant hit, as other skiers and curious onlookers immediately joined in.

Realizing they needed a bigger, more promising peak, the club moved to nearby Prongua and its namesake hill. It, too, quickly proved to be too small for their fast-growing ski community. So Dr. Zacharias and Mr. MacIntosh took flight in the good doctor’s airplane in search of a better hill. They narrowed their search down to two sites and eventually chose the smaller hill for one very big reason: water. With uncanny foresight, they realised that to succeed, their as yet unnamed hill would need water for snowmaking. Remember: this was 1969, when every respectable Western skier knew that snow came from good old Mother Nature, not artificial snowmaking guns.

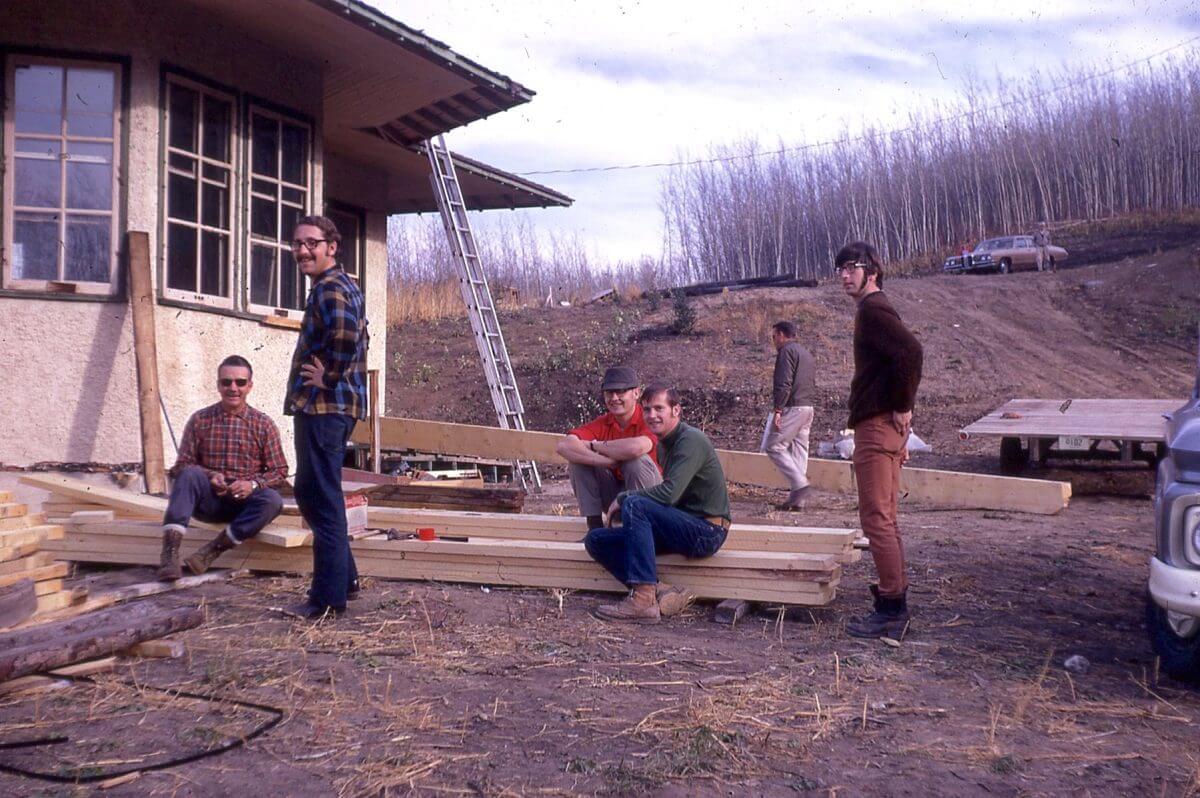

Pictured: Irwin MacIntosh in the 1970s at Table Mountain

Fuelled By Tireless Volunteers

Run and financed almost entirely by volunteers, the club leased the land, bought and moved the old Battleford Grand Trunk railway station, converted it into a ski lodge, cut trails and erected a rope tow. On January 1st, 1970, Table Mountain officially opened for business. It was such a resounding success that the club had to improve the access road, add another rope tow and, to quote a fellow Prairie trailblazer, “put up a parking lot.” They also agreed to let Hunter’s Sport Shop provide the rental gear.

According to Lawrence Blouin, GM Table Mountain, the ski hill is managed as a regional park with board members appointed by the cities and rural municipality. “But if you look at our clientele, we’re not really a community ski area anymore; probably 85 to 95 percent of our clients are an hour to an hour-and-a-half away.”

Pictured: Road being cleared at Table Mountain

A Change Of Ownership

Despite Table’s rising popularity, the club was hurting financially, so it asked the provincial government to declare the area regional parkland. In March 1973, the Battlefords Ski Club sold their hill to the newly established Table Mountain Regional Park Authority for $60,000. The club then invested all that money in the new park. Says Lawrence Blouin, “the original deal called for a 60/40 split. If the club applied for $100,000, the government would pay 60 percent and the club would pay 40 percent.” The other proviso was that, “the hill would have to be self-sufficient.”

Working with the province, the club established a racing program and a Nancy Greene League. They installed an airless snowmaking system, built ski jumps and hosted hundreds of nordic and alpine competitors for the 1974 Saskatchewan Winter Games. More impressive still is that for every dollar the government invested, volunteers also donated five dollars worth of their time.

Pictured: Chairlift installation

Hard Times Call For Special Measures

In 1981 the park was once again struggling financially. It asked the cities and boroughs of Battle River for help, and received about $64,000. Says Lawrence, “that’s the only money the regional municipalities have ever put into the park.”

To become more self-sufficient, the club took over the rental shop and concession. Says Lawrence, “that’s when we started taking off. We paid off our mortgage in 1985, but we were still getting a bit of government funding through the regional park system.” Skier visits soared as folks from as far away as Saskatoon and halfway to Edmonton flocked to discover Table’s new chalet and chairlift, its bountiful man-made snow and more.

Pictured: Picking the Saskatchewan ski team, Spring 1971.

No More Provincial Funding

Table Mountain Today

The Early Years